The road turns us through fields so dense with sunflowers and ripe corn that an American like myself could almost think I am strolling through central Kansas. But then the sidewalk shoulders us up to a distressed brick wall, on the other side of which we can see a compound of drab brick dorm-ish buildings with sooty windows and wirey, grotesque trees peeking out above them. The hair stands up on the back of my neck, and I look to the pilgrim beside me, who marches with a rosary in his left hand and a big white and red Polish flag in his right. “Is this it? I ask.”

“Yes, he says, this is Auschwitz.”

I am one of hundreds walking from the local Franciscan friary of Hermeze to join thousands for mass in front of Cell Block 11 in Auschwitz on August 14th, the anniversary of St. Kolbe’s execution and the eve of the feast of the Assumption of Mary. I am here because, for some reason, Kolbe’s story has both haunted me and given me hope for many years, and I am seeking, like all of these other pilgrims beside me, to understand where this man’s courage came from. My curiosity comes from a different place than many though. Back when Catholic Creatives was just getting started, we held a vote about who should be our Patron, and in an unexpectedly controversial voting process, St. Kolbe rose to a close second with Our Lady of Guadelupe. Though OLG edged him out for the win, I had to admit, there was something undeniably appropriate about Kolbe as a patron for CC. This was a man who championed the use of new media- who draw a surprisingly viable design for a rocket ship while in seminary approximately 60 years before we landed on the moon, and who made notable innovations to the printing press in order to better distribute his daily magazine to 600,000 families, who built one of the first Catholic radio stations ever, and who was planning on getting into film fifty years before Mother Angelica founded EWTN. A man who founded the first Franciscan manned fire station, who learned Japanese, and who eventually became the message himself when he volunteered to give his life to join another nine men in a starvation cell. Even then, I still wasn’t sold.

We put out all types of fire, but putting out hellfire is our favorite.

Before the procession on Kolbe’s feast day, I stayed a night in Niepokalanow- the Friary St. Kolbe founded and that still produces his magazine. After a night on a simple cot and a breakfast of tomatoes, cucumbers, and orange juice, I met Sr. Annmarie in the stout two-story museum that once housed Kolbe’s magazine printing machines. As we walked past walls lined with childhood paraphernalia and black-and-white photos from St. Kolbe’s seminary years, I was struck by the photograph of a friar, not Kolbe, sitting down and drawing with his pointy hood pulled up over his head, darkness enveloping his face. “Who is that? I asked Sr. Annmarie. “Oh that is the friar who helped Kolbe illustrate the covers of his magazine. Here he is with Kolbe- the three first founders of Kolbe’s Militia!” She said, and she pointed to a near life-size picture of Kolbe, his artist, and their third partner.

The contrast between the two other friars and the artist was so stark that I laughed. Even in a friar’s frock, the artist stuck out like a sore thumb. HIs unkept beard, strange expression, and grave eyes gave him the look of a metal-head gone Franciscan. I was struck by a thought that had been dawning on me since I first started becoming curious about him: Kolbe wasn’t just a creative type himself- he was a patron of, friend to, and partner with artists. In his early days, even before anyone knew that his magazine would be anything other than another passionate seminarian’s idea to “start a movement,” Kolbe was picking the weirdest, most creative friar’s out of the crowd and was enlisting them as friends.

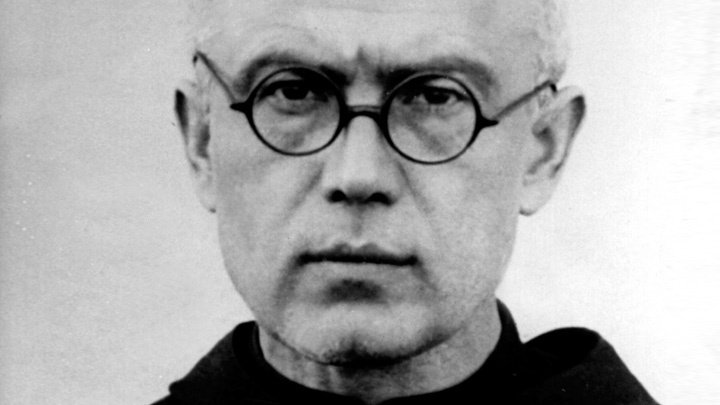

As many of us have learned, creatives tend to dwell on the extremities of the Church, at the edges, where they are easily misunderstood or even rejected as threats. Many people from the CC community can attest to how easily this creative rejection can happen in religious life or other Church institutions. The unpredictability, uncomfortable truth speaking capacity, and bohemian, chaotic manner that tends to be a part of the artistic persona isn’t the normal speed institutions are used to seeing. I think that part of why it took me a while to come around to Kolbe was because he didn’t look at all like my people- his close cropped hair, militant face, and severe expression in his pictures turned me off. But as I learned every step I took to come closer to Kolbe, he may have a militant, and rather heady style of writing, but as a man and as a friend, he was unbelievably inclusive, and he apparently liked working with edge dwellers like me.

Nothing says “creative” like round glasses

Mass was outside on the main cobblestone road of Auschwitz, between the lurching brick cell block buildings lined with more eerie, twisted trees. Hundreds of white and red flags flapped above the crowd, with flagpoles all decorated with the same feudal spirals of red and white. I perched myself beside a Polish boy-scout on the stairs to Cell Block 9, and as Polish choir chanted a melancholy Kyrie, I tried to square all contradictions before me. I was surveying the most horrifying, inhuman darkness that I could imagine, and yet, drawing closer to Kolbe’s beautiful expression of faith that is now being celebrated by thousands at a Catholic mass lead by a choir of the most angelic, earnest voices. For some reason, the brooding face of Kolbe’s artist came back to me during that chant. I felt a camaraderie with the man. I wish I had learned his name.

What eventually drew me to Kolbe was not his hard nosed battle with the Freemasons, or even sacrificing his own life to save Franczisek from starvation. It was actually this very broadness that began to draw me in as I learned more about the message his sacrifice meant to the people in Auschwitz, and to the people of Poland as a whole. I imagine that this unnamed artist in Kolbe’s friary might have felt the same thing as I did when they met, underestimating him, or boxing him up with all the other skinny and stern champions of faith one might meet in a seminary or friary. I wonder what little way Kolbe might have demonstrated his willingness to enter into the darkness of others' suffering that melted this metal-head friar’s heart, and then made him wonder, like I do now, where does this man’s love come from? When communion comes it isn’t really a line so much as it is a jockeying for position. We waddle forward like pigeons on a square flocking to a child dropping torn pieces of bread on the ground. The priest spoke something unintelligible to me, and I said amen and received the Eucharist, asking Kolbe to bless me, and as I tasted it, I cannot explain what I felt next. As woo-ey as it sounds, I felt Kolbe kiss me. Right there, only feet away from where he stepped out of the role call line and volunteered to starve and die in another man’s place, I was closest to him that I’ve ever been. Memories of my own dark nights of grief, suffering, insomnia, anxiety, and depression came to my mind, and I felt known. Kolbe, like Christ entered into darkness, and through his willingness to take on suffering, he stretched across the chasm that suffering and sin have opened, and he became the bridge from that darkness into heaven.

As I left that place, and found a new way back to the friary on the hard stubble of newly harvested hey, butterflies and bees marshaling about, I knew that were Kolbe here now, he’d have a place for me in his paper, if I were willing to join him in his poverty. Perhaps the deepest lesson that I’ve learned from him is that for some mysterious reason, the darkest evil can be conquered by a single love, the same way that a single match can put out the darkness, the way that a single man’s hope could bring thousands to trample on the evilest streets ever made, and sing in one accord, Holy Holy Holy is the lamb.

Jin Dobra,

Anthony.